Johann Christian Schoeller, "Sonnenfinsternis, 8. Juli 1842." Wien Museum.

*

John Parker Davis, "Looking at the Eclipse (After Winslow Homer)," 1865. Clark Art Institute.

*

*

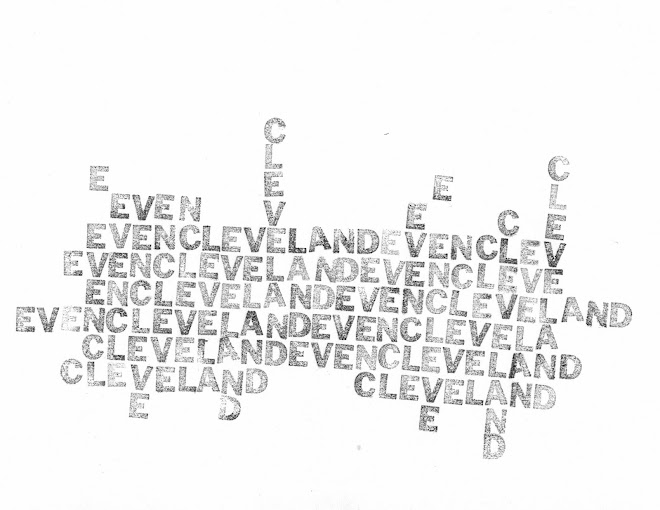

Emily Dickinson archive, Amherst manuscript #256.

*

*

GIFs from Georges Méliès L'éclipse du soleil en pleine lune (The Eclipse: Courtship of the Sun and Moon) from 1907.

*

At one o'clock almost half the sky was blue—two o'clock, and the moon had already bitten a small piece out of the sun's bright edge, still partly obscured by a dimly drifting mass of cloud.

A penetrating chill fell across the land, as if a door had been opened into a long-closed vault. It was a moment of appalling suspense; something was being waited for—the very air was portentous.

The circling sea-gulls disappeared with strange cries. One white butterfly fluttered by vaguely. Then an instantaneous darkness leaped upon the world. Unearthly night enveloped all.

With an indescribable out-flashing at the same instant the corona burst forth in mysterious radiance. But dimly seen through thin cloud, it was nevertheless beautiful beyond description, a celestial flame from some unimaginable heaven. Simultaneously the whole northwestern sky, nearly to the zenith, was flooded with lurid and startlingly brilliant orange, across which drifted clouds slightly darker, like flecks of liquid flame, or huge ejecta from some vast volcanic Hades. The west and southwest gleamed in shining lemon yellow.

Least like a sunset, it was too sombre and terrible. The pale, broken circle of coronal light still glowered on with thrilling peacefulness, while nature held her breath for another stage in this majestic spectacle.

Well might it have been a prelude to the shriveling and disappearance of the whole world—weird to horror, and beautiful to heartbreak, heaven and hell in the same sky.

Absolute silence reigned. No human being spoke. No bird twittered.

Hours might have passed—time was annihilated; and yet when the tiniest globule of sunlight, a drop, a needle-shaft, a pinhole, reappeared, even before it had become the slenderest possible crescent, the fair corona and all color in sky and cloud withdrew, and a natural aspect of stormy twilight returned.

*

It sounded as if the streets were running -And then the streets stood still -Eclipse was all we could see at the WindowAnd Awe - was all we could feel -By and by the boldest stole out of his CovertTo see if Time was thereNature was in an Opal apronMixing fresher Air

Emily Dickinson